‘We are only beginning to know what it is’: Why doctors struggle to identify treatments for long COVID

Karen Weintraub USA TODAY

Published 9:00 am UTC Sep. 14, 2022 Updated 1:13 pm UTC Sep. 14, 2022

Liza Fisher was an international flight attendant and yoga instructor before COVID-19 pneumonia landed her in intensive care. With two stimulators implanted in her spine, she's relearned to walk and is finally advancing from a wheelchair to a walker.

It was so early in the pandemic and her case so mild that Cynthia Adinig was never tested for COVID-19. But after nine months of ruling out every other possible cause for her disabling chemical sensitivities and physical problems, her doctor agreed they were the result of the infection.

Pam Bishop was pretty sick with COVID-19 back in December 2020, developing severe insomnia, profound fatigue, nausea, horrible headaches and random, severe pains. She assumed they would all be short-lived. They weren't.

The three are among millions of Americans suffering from long COVID-19 – life-altering symptoms that endure for months or even years after an initial infection. Their different experiences show the challenge of helping people with a condition that creates so many profound and varied problems.

"We don't know how to treat long COVID. We are only beginning to know what it is," said Dr. Clifford Rosen, a professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston and a senior scientist at the Maine Health Institute for Research.

Although long COVID clinics have popped up in nearly every state, and the internet is filled with promises of easy fixes, there's still very little solid science about the condition. Medical care – if someone can get it – consists of trying to address each troublesome symptom on its own.

So, how to find effective treatments for a condition that includes a constellation of different problems, with symptoms that overlap other health issues, among millions of people, some of whom can't confirm they were actually infected and are at different stages of recovery?

Unfortunately, the answer seems to be: very slowly.

Federal research, backed by more than $1 billion, is on track to provide some answers in about four years – lightning fast by the standards of government research, but way too slow for people who are suffering now.

At least a handful of existing treatments might offer assistance much sooner, but no one is testing them at large scale.

In part that's because a study won't show clear results unless it includes the right patients. In some people, symptoms might be triggered by lingering virus somewhere in their body. But if that's the cause in only a fraction of people, a treatment might look like a failure if given to everyone.

Pharmaceutical companies have little incentive to launch research until the condition and measures of improvement can be clearly defined. And many of the existing drugs that might be useful are off-patent, with no promise of earnings for a company. So, there's little money to study them.

Long COVID patients like Bishop, Adinig and Fisher are growing increasingly desperate for a treatment that will not just mask their symptoms but solve their problems.

"My question is, what are they doing? What's the agenda? What's the plan here?" Bishop asked of the federal government. "They're not doing the things that would be the most helpful to the patients."

Federally supported science takes time

The federal funding system, while appropriately conservative in nonpandemic times, isn't set up to support "disruptive innovation," or to deliver change rapidly enough for the current situation, said David Putrino, director of rehabilitation innovation in the Mount Sinai Health System's Department of Rehabilitation and Human Performance. David Putrino, a senior author on the paper and director of rehabilitation innovation for the Mount Sinai Health System.

"The major funding source in the country has not been funding innovative and out-of-the-box thinking when it comes to helping us understand long COVID," he said.

Typically, federally funded research takes about 17 years to change medical practice, he said. "We need changes in clinical practice to come much faster than that in long COVID, but the NIH has not sufficiently changed their process to rise to the challenge."

The researcher leading the federal long COVID effort, Dr. Stuart Katz of NYU Langone Health, defends the pace of progress so far as "remarkable." The government-funded clinical research program, Recovercovid.org has already enrolled more than 8,100 adults and more than 750 children, toward a goal of about 17,500 to 19,500 respectively, both with and without long COVID symptoms.

That many people "in less than 18 months is a pretty monumental task," he said.

Adult enrollment should be completed by the end of the year or early next, with childhood enrollment some months behind.

"This is a little later than our original expectation, but our original goals were very ambitious," Katz said.

The volunteers are racially diverse, so far, he said, with 54% white, 13% Black, 10% Hispanic and about 5% Asian, roughly equivalent to their percentages in the general population, though underrepresentative of Hispanics.

A "biobank" of samples will be used to answer questions about what's causing the range of long COVID symptoms, as well as to develop tests to objectively identify people with the condition, he said.

Once identified, the government can launch treatment trials, Katz said. Diagnostic criteria also are essential for helping patients get disability coverage from Social Security.

This month, the federal government awarded a $9 million, 5-year grant to the Regenstrief Institute, of Indiana, to study the incidence of long COVID, using medical records and by tracking COVID-19 patients.

"The definition of what is long COVID does not exist yet," said Dr. Shaun Grannis, who is helping to lead the effort.

The federal government is making a point of including patient input, which often didn't happen in the past, said Dr. Michael Iademarco, a rear admiral and deputy assistant secretary of health.

"It might slow us down relative to the way we might have done it," he said, "but we're going to get better outcomes.

Who’s getting long COVID

Recent studies suggest about 5% of people who caught the omicron variant and nearly 13% of those who got the original or alpha variant still had symptoms more than three months after infection. Since more than 57% of Americans are believed to have been infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in its first two years, that adds up to millions of people with long-term suffering.

Every new infection carries a new risk for long COVID, research shows. Vaccinations seem to reduce the likelihood of long COVID, but it's still unclear by how much. (One study from Israel found no difference in long COVID symptoms between uninfected people and those who had been vaccinated twice before being infected.)

There's no firm data on how many people continue to suffer after a year or more or are permanently disabled because of long COVID. Estimates suggest that somewhere between 7 million and 23 million Americans have the condition and at least 1 million are out of work because of it. Children can get long COVID, too, though much more rarely.

Another recent study, which hasn't yet been peer reviewed, suggested lingering symptoms may differ by variant. For instance, while lung damage was common early in the pandemic, before vaccines became available, it is less common among people infected more recently. Other research has suggested that loss of taste and smell has become less frequent with more recent variants, but more than 10% of people who lost their smell in the first wave still haven't recovered it two years later, another study found.

Men seem more likely to get severe COVID-19 infections, while women are more likely to suffer from long COVID, studies show, and people ages 18-30 may be at highest risk for long COVID.

It's not clear whether there are differences by race. Dr. Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, a physiatrist, works in San Antonio, a city that is 60% Hispanic, but only about half her patients are Hispanic.

She's not sure whether that lower rate reflects the actual suffering, or because Hispanics have less access to medical care. Perhaps they lost their job because they didn't have paid sick leave when they caught COVID-19, or they lack the health literacy to research their condition and seek care, said Verduzco-Gutierrez, chair of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at the Long School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio.

The more symptoms someone has after their initial infection, the more likely they are to linger, research suggests.

"You have to get it addressed right away and have it be controlled," Verduzco-Gutierrez said. "The longer they go on, the longer it's going to continue."

Lack of clinical trials

There are essentially no large-scale studies of potential long COVID treatments, and people with severe symptoms feel less hopeful that answers will come in time to help them.

"Two and half years into this pandemic and we are only starting to plan clinical trials. What's wrong with this picture?" Rosen asked rhetorically.

What's needed, he said, is more energy and money – he estimates about another $1 billion – to find science-based treatments for long COVID symptoms.

In August, the Biden administration released a report on long COVID, laying out many of the challenges that need to be addressed. Treatments were on that list, along with a dozen other issues.

Advocates and experts praised the report, but said it didn't go far or fast enough.

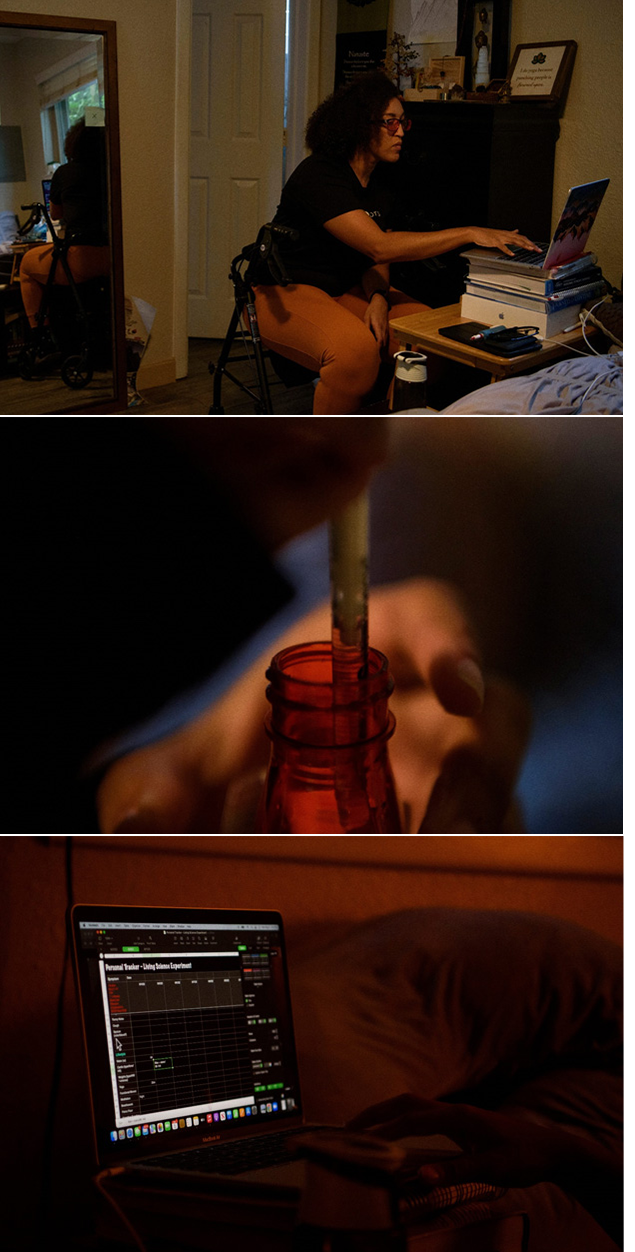

Cynthia Adinig opens a bottle of antihistamines, one of many medications she has placed throughout her home for easy reach in case she or her son have a flare up of symptoms from long COVID. JOSH MORGAN, USA TODAY

Rosen and others called for pilot trials that could help narrow down some of the more obvious possibilities to see whether they might be helpful.

Anecdotes suggest that the antiviral Paxlovid, which has proven effective at preventing hospitalization from COVID-19 infections, might help some people who haven't been able to clear the virus on their own. Similarly, booster shots have helped some people with long COVID.

But neither has been systematically studied for long COVID and Pfizer, which makes both the antiviral and a leading vaccine, will say only that it is "considering multiple collaborative studies to evaluate potential treatment for long COVID."

A year ago, the government promised it would launch clinical trials, but the website for volunteers appears to be a dead end, said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease specialist with Northwell Health in New York.

"I registered myself and nothing but crickets," he said. "I'm just not sure where that money is and what's going on."

"People are so desperate and they so much want to be part of the solution," but they're not seeing trials they can join, Griffin said. "It really is disheartening."

An expert panel should be convened immediately, establishing criteria and objective parameters, rather than debating the definition of long COVID, said Dr. Saurabh Mehandru, a gastroenterologist and researcher at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Then, they should launch clinical trials of multiple likely treatments, he said. "We have more than enough information – we have almost an overwhelming amount of information – to start trials."

Instead, interest in COVID and its lingering effects seems to be fading, said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a cardiologist and director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, which focuses on improving patient outcomes and promoting population health.

"We're not in a better position for patients than we were a year ago," Krumholz said. "I am concerned that many research funders don't feel the same urgency about long COVID. The novelty may be gone, but millions of people are still suffering – and those numbers will grow as the infections continue."

Treating long COVID

The American medical system is built around a primary care doctor sending patients to a specialist, as needed. But it's not clear who should see patients suffering from extreme fatigue, exhaustion after minor activities or lung or heart problems that don't show up on a typical scan, Rosen said.

Uncertain what to do to help, many primary care doctors still wonder whether to forward a patient to a specialist or if their condition is mostly psychological.

It's definitely not, Rosen said, but "our system is not built for this type of uncertainty and chronicity. We expect people to get better and get better quickly."

A long COVID patient can't be treated in a simple 10-minute primary care visit, Verduzco-Gutierrez said. Doctors need more support, too. "Otherwise, your PCP is going to go, 'I don't know, and I have three people waiting for me. I can't deal with your shortness of breath and your headaches and your insomnia and your fatigue and your joint pain today.'"

At her clinic, there is at least a four-month wait to be seen, Verduzco-Gutierrez said. Patients need multiple visits to treat their range of symptoms, and more people are developing long COVID with every wave of infections.

Dr. Clifford Rosen

Our system is not built for this type of uncertainty and chronicity. We expect people to get better and get better quickly.

Insurance can be another impediment to care. Verduzco-Gutierrez would like to prescribe a treatment called EECP for patients with fatigue or blood pressure fluctuations, for instance, but insurers will cover it only with a diagnosis of angina, whose criteria many of her long COVID patients can't meet.

Existing treatments can address many of a patient's most bothersome symptoms, and most long COVID clinics usually start by tackling these, Griffin said. Migraine medications can help some people with headaches, histamine for rashes, other medicines for those with gastrointestinal issues, for instance. "There's definitely stuff you can do" as a doctor, he said.

But there's still nothing specific or scientifically proven to treat some of the most debilitating long COVID symptoms, he said. He had little to offer a teenaged patient who was a dancer before catching COVID-19 and now can't sit up in bed for more than 45 minutes without projectile vomiting. Another patient was a college professor who has such brain fog she can't sign her name on a check.

"Part of it is not dismissing them," Griffin said.

Patients taking charge

While waiting for help from experts, patients are helping each other.

After an article about Adinig appeared in The Washington Post in December 2020, a group representing people with chronic fatigue syndrome reached out to her. Suffering for years from similar symptoms, they could offer the wisdom of experience.

Adinig, now 37, of Vienna, Virginia, had been coping for months with a sore throat, gargling a few times a day and wrapping a scarf around her neck to provide a little relief. The chronic fatigue advocate suggested she might have developed a chemical sensitivity and to avoid all perfumes and fragrances in things like soap and shampoo.

Two days after getting rid of scented products, her sore throat was gone.

"No doctor would ever have been able to say that," she said.

Chronic fatigue sufferers also taught Adinig, a marketing specialist, how to truly take care of herself. When she was infected in March 2020, she was writing a book, running two businesses and parenting a 4-year-old. She always kept a spotless home and had done whatever she could for friends, family and her church: "I was the helper person. If my friend ever needed something, I'd move heaven and earth."

After COVID-19, her body was telling her it needed rest, Adinig said, but "it's so hard to do."

It's unclear how many people continue to suffer as long as Adinig has, but most long COVID patients recover eventually, Griffin said: "Whatever we do, there is a percentage of people who do get better over time."

Pam Bishop

I feel like long COVID is killing me cell by cell. It’s like living this very long, drawn-out death.

Fisher, 38, of Houston, is making slow, incremental progress and hoping for no more setbacks. She recently stopped needing to see her primary care doctor weekly, but continues to attend a brain injury clinic and her cognitive struggles continue.

"On a good day, I'm maybe 80%," she said, adding that those days come perhaps one weekend a month. "On a bad day, more like 50-40%. I forgot how old I was the other day. Things that I wouldn't normally do."

Bishop, 46, of Knoxville, Tennessee, believes she's getting worse rather than better. She has less energy than she did even at the beginning of the summer. "Almost anything I do puts me in bed," said Bishop, who ran a research institute before being disabled by exhaustion. "There's just nothing left to give.

"I feel like long COVID is killing me cell by cell. It's like living this very long, drawn-out death."

Long COVID is real

Although Fisher, Bishop and Adinig took different routes to long COVID, they share similar stories of not being believed by medical professionals; of doctors changing their medical records to conform to standard diagnoses rather than their actual experiences; of defending their need for care, and that their problems were physical not psychological or attention-seeking.

Bishop went to her primary-care doctor with a list of problems: fatigue, pain and gastrointestinal issues, nausea with exercise and dizziness when standing. Her doctor had nothing to offer but an antidepressant.

Fisher wishes doctors would "have transparency to say 'I don't know what to do, but I'm going to help you figure it out'" – a request Adinig and Bishop repeated.

Cynthia Adinig

A lot of people could have recovered by now had they gotten to the clinics earlier, had they had a doctor listen earlier.

PHOTO BY JOSH MORGAN, USA TODAY

Experts have absolutely no doubt that long COVID exists and can create serious and long-lasting problems.

"Top-line slogan: Long COVID is real," Iademarco said.

Krumholz said that when he acknowledges a patient's suffering, some are so relieved they burst into tears.

"I feel embarrassed that such a little sign of acknowledgement could mean so much," he said. "It signals to me how much these people must be feeling alone and alienated from the current system to have that kind of reaction."

This medical disconnect has consequences for patients.

"A lot of people could have recovered by now had they gotten to the clinics earlier, had they had a doctor listen earlier," Adinig said.

It's particularly challenging for Black women to be believed in the medical system, Adinig said. Her primary care doctor was helpful, but when she repeatedly sought help for pain in emergency rooms and while hospitalized, she was either treated as if she must be imagining it, or as if she was hysterical and dangerous.

"There's literally no way we can approach care and get it," she said. "We're going to have hurdles every step of the way."

It took nine months for her primary care doctor to rule out any other possible cause and find specialists who would support her. Meanwhile, several white friends with similar symptoms were getting treated. They recovered; she has not.

To help others know they are not alone in their suffering, Bishop takes any opportunity she can get to talk publicly about her condition. She can afford to speak out while others can't, she said, because she has nothing left to be taken – she's already lost her job, her career and some friends.

"It's the one thing I can do," Bishop said. "Long COVID is real and it's devastating and people have it and we need research and we need therapeutics. And ultimately, we need a cure."

Published 9:00 am UTC Sep. 14, 2022 Updated 1:13 pm UTC Sep. 14, 2022